OPEN THE DOORS

On the 14 June, we were invited by Olga to visit Bulgaria's only stone-cutting school in Kunino. Located an hour from Sofia, the capital, this school has a long history of stone-cutting and a heritage that pays tribute to the knowledge and skills of craftsmen and artists.ste de blog.

TRAVEL DIARY

Orianne Pieragnolo

11/15/20234 min read

View of the mountain from the boarding school.

On 14 June, we were invited by... to visit Bulgaria's only stone-cutting school in Kunino. Located an hour from Sofia, the capital, this school has a long history of stone-cutting and a heritage that pays tribute to the knowledge and skills of craftsmen and artists.

You have to imagine being in the warmth of the June sun, where the rays are hot and still fresh. They pierce the windows of the dusty train that takes us to the small town of Kunino, in north-western Bulgaria, not far from Sofia, the capital. We pass through a dense, green and rich landscape where mountains, like sugar loaves, tower around us. One of them greets us on the station platform. Majestic and imposing. It's there to announce the mineral presence of the place. As if to tell us that yes, you have arrived. This is where hands learn to handle the material that makes up its side. Because on this day, 12 June 2023, we have an appointment with Olga, one of the teachers, at the Kunino School of Stone Crafts, the only one of its kind in the country.

All we have to do is cross the tracks to find the school. A large gate with a sign indicates the name of the school. In the entrance courtyard, the first thing we see are pans, their feathers fanned out, next to sculptures stored on the ground. We enter the alleyway where many workers come and go. The premises are being renovated.

The school is housed in a large, cloister-like, single-storey building. An inner courtyard opens up the corridors to natural light. Sculptures adorn every nook and cranny. Outside, at the far end, a dilapidated building in the style of the 1970s serves as a boarding school. In the park, sculptures and stone-cutting projects are on display everywhere. There's a fountain, a kiosk, busts on pedestals... all testifying to a past activity and knowledge.

This large space is a truly romantic showcase for what you might imagine being a school of sculpture and stone-cutting. Everything has remained as it was. But the way the building is occupied contrasts with its appearance. You'd like to see lots of students and hear tools banging through the workshop doors, but all you find are a handful of students, around fifteen, with cleats tucked away in the corners of the rooms. The contrast suggests a certain nostalgia.

We have an appointment with Olga. Dynamic, in her thirties, she too seems passionate about her job. Or rather her professions. Olga is first and foremost a sculptor. She is a teacher, but also works on her own in various artistic fields, such as painting and pottery, in which she tries to excel in each of her works. She becomes our Bulgarian mentor.

At the moment, we're in a hurry,

The three of us are invited to sit on the sofas in the office. Like everything else, we have the impression that the space has been frozen in time. But as the discussion progresses, we come to understand this place much better. As the story unfolds, the pieces of the jigsaw come together around the story of Kunino's school.

Indeed, this school carries the heritage of a culture of stone skills and is the mirror of several eras through which the country has passed. It all began in 1920, when the school was created to modernise stonework and meet the growing needs of the market. A Czech sculptor, Rudolph Braun, was called in to head up the company in order to train it and bring it international recognition. At the time, the Czech Republic had a strong reputation in the stone industry. The foundations were laid with a few students. Over the years, the school grew in size and reputation. It trains numerous Bulgarian stonemasons and sculptors. Prestigious directors, renowned as sculptors and builders, followed one another. In the 70s and 80s, the school welcomed more than 300 students to its premises ! It was the golden age of schools and stone. The train next door brought the blocks of stone and created a link with the capital. It was still the communist period, and sculptors and stonemasons were in great demand to meet government orders. Most of the students who came to the school were destined to go on to the Beaux-Arts or to further study. The school's reputation spread beyond its borders.

But the end of these glorious times came at the same time as the fall of communism at the beginning of 90. Since then, the school has gradually emptied out, the need for stone specialists has diminished, and as in many other countries, craft courses have suffered discrimination in the face of more theoretical courses.

Today," says the director, "it's not easy to teach the students here, most of whom didn't choose to be here. However, hopes of revitalising the school are not waning. Work is being done to modernise the premises, and a number of strategies are being developed to attract motivated students and breathe new life into the school.

After the visit, we were very moved by the message of hope and the extraordinary possibilities that the site can offer. The idea of a European meeting of stone professionals and apprentices, or a festival, was obviously on our minds.

The knowledge and the teachers are still there, and we shouldn't let such a heritage disappear into oblivion.

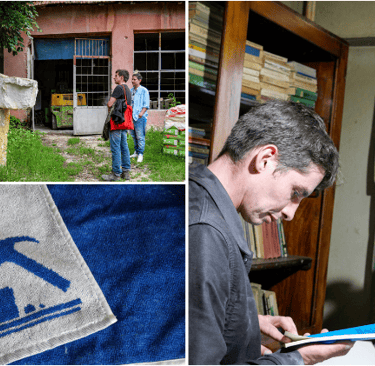

From left to right: A visit to one of the school's warehouses / A visit to the school's archives / The school's towel with a design referring to stonemasonry.

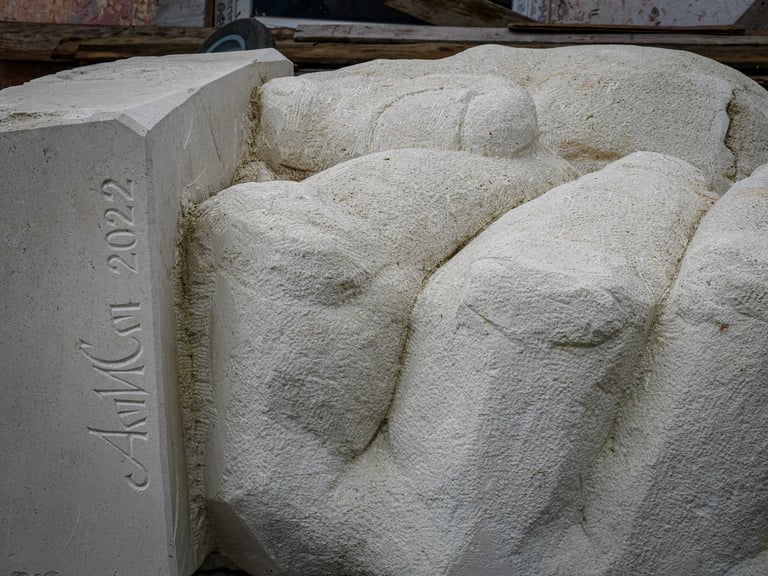

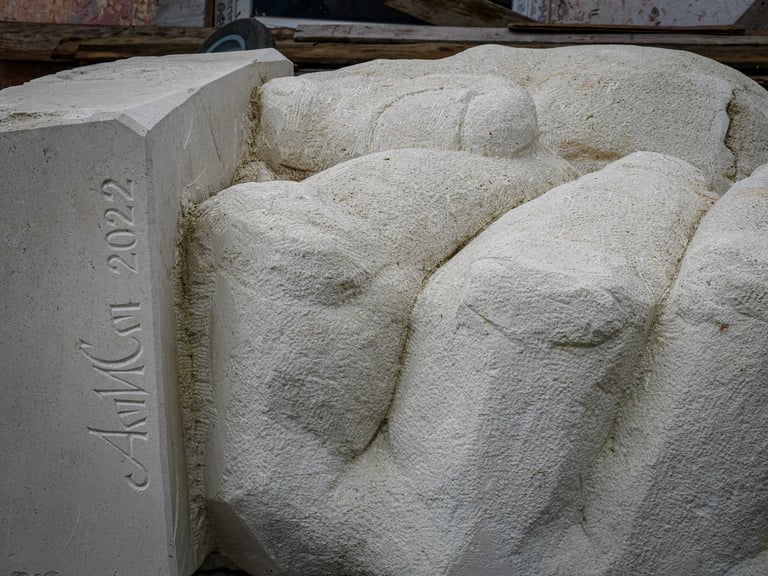

Various views of the school, its workshops and grounds.

Do you like our articles?

Help us by offering a coffee!

Follow the project ...

Editorial by the La Route de la Pierre team

©️La Route de la Pierre | Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | General Terms and Conditions of Sale