LEARNING THE BASICS

We invite you to come and discover an important part of Georgia's heritage: Georgian ornamentation. It's an art and a skill combining stone-cutting, sculpture and engraving. Specific to the country, it reflects the many exchanges between peoples, but also symbolizes a part of Georgian culture today, as evidenced by their presence in detail on official passports.

TRAVEL DIARY

Orianne Pieragnolo

8/12/20245 min read

The end of June saw our arrival in Georgia and with it the start, the real start, of the expedition. Almost a month had passed since we left France and reached the shores of Batumi. When, from the ferry bridge, we could make out the town, we knew that the second stage was about to begin. The panorama was striking. Multicoloured cranes towered over the rusty hulls of huge ships, sending containers flying to the ground. The atmosphere of the commercial port was just a few metres away from the chic space of the yachting quays. On their edges, the brand new buildings tried to defy the mountain peaks that could be seen on the horizon. We understood that contrasts build cities. Now we're going to discover that they also shape life in the city.

Choosing to travel by land and sea certainly helped to make it easier to understand that we are at a crossroads, right in the middle of Eurasia. The country is blocked to the west by the Black Sea and to the east by the Caucasus. It is an essential passageway between two giants, Russia to the north and Turkey to the south. The land here has lived, been invaded and reconquered, but above all, it has welcomed. Millions of travellers, traders, emissaries, men and women have passed through. Some had to stay, others left. Despite this history, a strong culture has developed, including a language and one of the world's forty alphabets.

Are we at the centre of the earth?

If we are descended from the stones, as Apollodorus tells us, then perhaps a closer look at them will tell us?

Ornamentation by Torniké Madchaïdze

The arrival

From left to right: Vine, one of the main ornamental subjects; stylised vine leaf; Church of Ozurgeti, span matching that of the trees; Detail of a column in the stone-cutting workshop of Tbilisi Cathedral; Small clubs used by Torniké; View from the mountains of the Ateni valley; Part of Mount Atos being cut; Interlace of trees.

Between plants and architecture

We were back on the road, determined to unravel this mystery and meet both the stones and those who transform them. Also, we had to leave behind the mountains that encircle Batumi. We gradually left behind the density of inhabited streets, their noise and teeming activity, and entered the green luxuriance of the Georgian countryside. The surrounding nature was resplendent, like a reflection of the profusion of a Garden of Eden. For in these lands, we are told, mankind was able to develop its cultivation skills before many other territories. Is that why the trees have grown out of the forests to occupy the towns and villages? In the streets, vines run along the lampposts and keep their place above the terraces to protect the heads of the inhabitants from the sun. Wine has been produced here for eight thousand years¹.

The osmosis between nature and the intertwining vegetation can even be seen on the

the facades of the churches. We're discovering it as we go.

¹ The tradition of kvevri wine-making was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. It defines the way of life of local communities and is an inseparable part of their cultural identity and heritage, with vines and wine being evoked in Georgian oral traditions and songs.

Left and right: Details of ornaments from a new church, but left to rot. In the centre, Torniké Machaidzé carving a Saint George.

At the crossroads of influences

The language of know-how

Churches spring up everywhere. All you need is a square, a hill, a mountain or a peak to welcome their stones, whether they are recent or thousands of years old. In Georgia, the main religion is Orthodoxy. This is important for us, as stonemasons, because we're going to understand the extent to which this information can influence the profession. From plans to details, the rules of the region dictate and govern the forms of architecture. Just like politics, it shapes aesthetics in order to orient them around ideas, a culture and/or a cult.

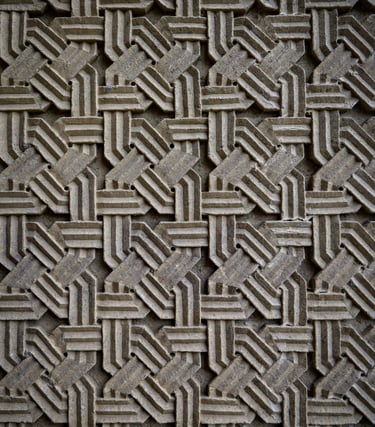

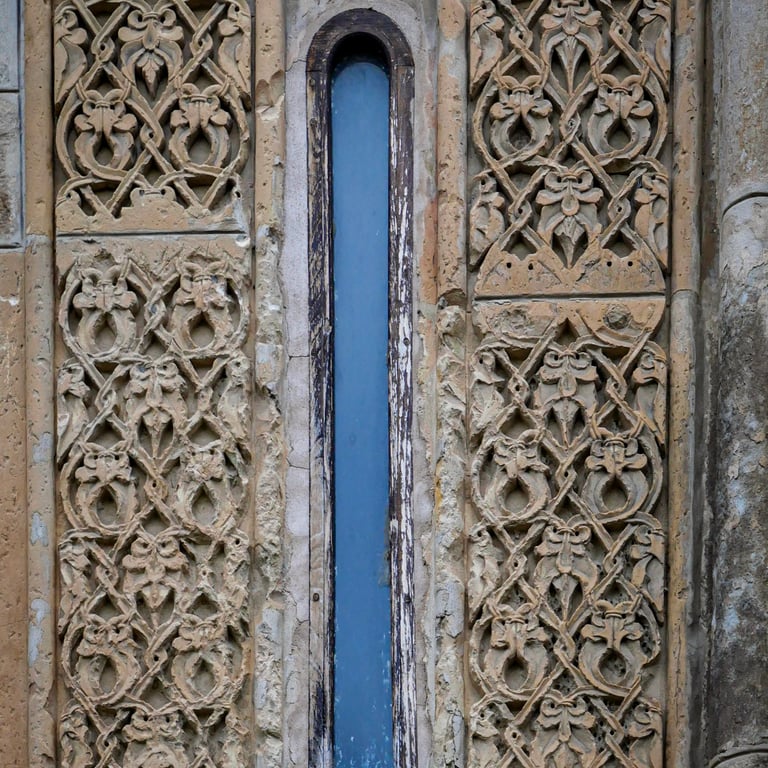

We are therefore discovering ecclesiastical architecture that often uses the basilica plan. But the distinctive feature is not to be found in the structure, but in the walls. It's the Georgian ornaments. They are the ones that jump out at us. They are figurations that allow us to imagine a reading and a transmission of stories.

Through their forms, we try to decipher their language and understand their origins. First of all, we see a melting pot of influences. The presence of horseshoe arches², which can be borrowed from the East, and the charged, almost Celtic interlacing, bring back Western forms, while certain capitals or pillar heads, with their rounded cut-outs, are reminiscent of East Asia. One thing that unites and unifies them all is the compositions, which are governed by strict rules. One of these comes from the clergy, who only authorise representations in the form of low or high reliefs⁴. The round hump³ is forbidden in Orthodox places of worship, replaced by icons. Mouldings are also becoming rare here, replaced by the interplay of interlacing and low reliefs. These forms are also found in certain public buildings, some of which even date back to the Soviet era, making the old styles part of an extremely strong local and cultural heritage.

The sight of all these ornaments overwhelms us, and above all, challenges us. There's a lot to learn. You can't approach a crossroads of civilisation like this in a few months.

We had to meet a master specialising in ornamentation, Torniké Madchaïdze, to gain a better understanding of their complexities. And with him, we came to understand one essential thing: the craftsman's freedom of expression. Torniké not only masters the cutting of his stones, he also knows how to invent and compose his ornaments and icons. He knows the codes and curves, the right play of light and shadow. Freehand, he traces his subjects directly on the stone. By mastering his creations, he demonstrates a high level of expertise. But he also shows sensitivity, faith and love for his craft. The results are touching.

The architecture we came across did not leave us indifferent either. Could this knowledge be one of the ways of getting to the heart of the matter? Would composing, without reinventing, but inventing on the basis of millennia of experience, enable us to perpetuate the dialogue offered by the craftsmen on the façades? Stones speak... If they are cut without meaning, they lose all voice.

One evening, Torniké shows us his passport. On the inside back cover, an engraving depicts the portal of a church in detail. It contains elements almost identical to those stored in his studio. You can see how Georgians treasure their ornaments, which are indelibly marked in a passport as proof of their identity.

²An arch whose centre point is below its birth line. This type of arch is very common in the Middle East, but also in India and North Africa.

³A sculpture with all sides cut out. It is completely in 3D.

⁴Engaged sculptures, they are not entirely free of their support. They cannot be walked around.

Discover the other articles ...

La Route de la Pierre newspaper

Discover the other articles ...

La Route de la Pierre newspaper

Do you like our articles?

Follow the project ...

Editorial by the La Route de la Pierre team

©️La Route de la Pierre | Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | General Terms and Conditions of Sale