Ausbildung und Meister

In Munich we were invited to visit and present the project to one of the stonemason classes. We also took the opportunity to better understand the organisation and value of training in Germany.

LOGBOOK

Louis Dutrieux

10/20/2022

We carried a tool in our bags that we had never used before: a digital recorder. It allows us to preserve the voice of the stonemasons, parts of their lives that they share with us. These are the experiences they tell us about and the advice they give us. Last summer, we sat around a garden table to interview a colleague. In his warm voice, he shared with us: "I think that being a stonemason can give you access to a dozen other professions". These words made an impression on us. They made us want to find out more about what German training courses can offer in terms of professional prospects.

These apprentices are thus enriched, over a period of three years, with experience and discovery of their professional world. In the end, they are able to think for themselves and have a broader view of the possibilities of the trade. Workers who decide to take on responsibilities later on must become a Meister (master in French). This status gives them access to a significant level of recognition within the profession. In Germany, this level is compulsory to open a company, to become a workshop or site manager or to train young people. It protects the quality of the companies, enables the expansion of personal perspectives and promotes innovations in the trade. In order to obtain the diploma, students acquire the necessary skills to instruct and undertake in two years. During an interview with an entrepreneur, he explained that he would like to retire. However, there is no one else in the company who has a Meister title. The manager's son will therefore have to have one in order to take over the family business.

Moreover, this professional level, recognised as a Bachelor's degree, allows access to university. This is a real asset for those who wish to enter another profession, but also for the stone sector itself, because it favours the recognition of professionals. In fact, we spoke to Jérôme, director of the Bauhütte in Passau. In his office, amidst plans and shelves of books, he explained to us what his studies in art history brought him after he became a Meister. The knowledge he gained at university, combined with his experience as a stonemason, now enables him to work with archaeologists and historians on the cathedral site. The title of Meister is therefore an asset for the recognition of practical knowledge in the country.

So we met several apprentices during our stay in Germany. Some of them had a clear idea of what they were going to do later on, while others were living their trade day by day, without asking themselves what they could do with it tomorrow. These students were still in the Ausbildung period (training in French), in the first, second or third year of training. During these meetings, we were able to observe that each stage of their learning is built around several initiatives. They lead them to develop their creativity so that each of them can find a path in the profession that corresponds to them. The alternation inherent in their apprenticeship forces them to take responsibility and to confront the trade. We understood this on the Lindau site, with Rosjna, the apprentice who worked with us. She showed us, with passion, her carefully hand-drawn tombstone designs to be presented to clients. Thus, every moment spent at the company increases her experience and maturity.

In the third year, the students have to complete their Geselle Stûck (Journeyman's Piece), a work that allows them to take stock of their learning periods. This work is presented as a personal reflection, a blank sheet of paper given to bring together the sum of accumulated experience, expressing the sensitivity and interest of each individual in a single piece. During the visit to the workshop of the Bauhütte in Passau, we spoke with Daniel, a third-year apprentice. He proudly presented us with the draft of his final project. He plans to make it in two parts, with gothic contours. Before ordering the stone, he plans to make several models to find the right proportions. His work is quite slim and slender, which reveals the character of the person and his potential.

Germany also brings together initiatives led by associations or organisations to promote the professions and offer further training courses. In this way they contribute to the defence and promotion of the interests of their profession. The guild (Innung in German) is an actor in this. For workers, there is also the German Compagnonnage, represented by various associations, including the Roland Schacht (Roland Brothers' Society), which offers a programme of advanced training courses open to Europe.

There are certainly many other possible courses and teaching paths for the trade. However, it can be seen that, regardless of one's status, whether as an apprentice or as a worker, as a company manager or as a workshop manager, it is always possible to move on to other specialities while remaining in the stone industry. This organisation of the profession also provides all its members with prospects for development and innovation. The German stone industry is therefore well equipped to take on the economic and ecological challenges of tomorrow in its own way.

Do you like our articles?

Interview with one of the "building technology" teachers in the school's stonecutters' workshop.

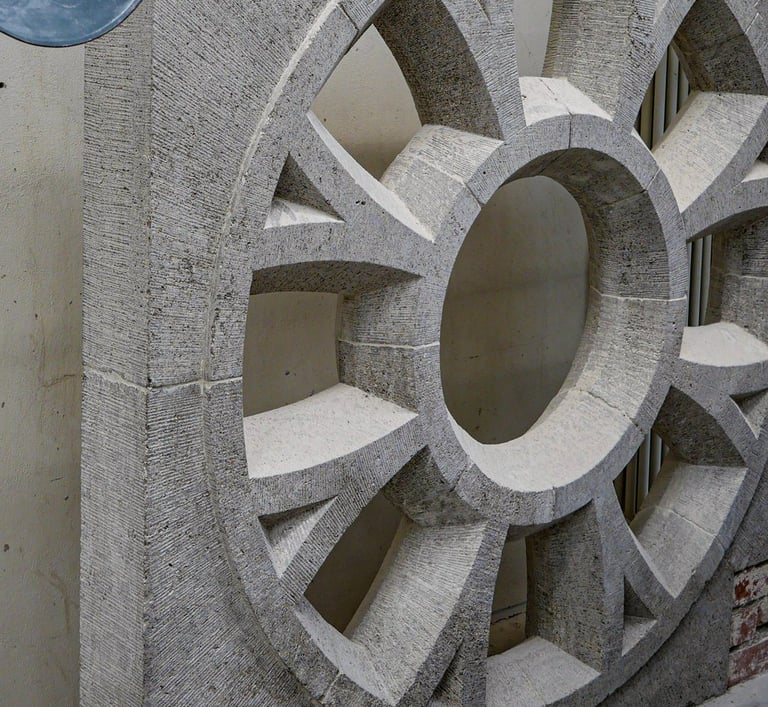

Details of the stonemasons' workshop at the Munich School of Building and Construction.

Apprentice of the Bauhütte Passau

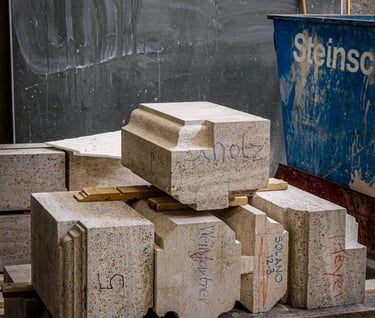

Exercise stones at the Munich School

Front of the Bauhütte in Regensburg

Follow the project ...

Editorial by the La Route de la Pierre team

©️La Route de la Pierre | Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | General Terms and Conditions of Sale